Part of a series: COVID-19 — Nurses’ Notes from the Front Line

by Stephanie Smith, RN

I’ve worked in the ICU at St. Joe’s hospital in Burbank, California, for more than four years. The ICU is everything I love about nursing.

I decided I wanted to be a Nurse after I received a liver transplant when I was 21. I saw how competent and calm the Nurses and other hospital staff were. I especially liked seeing how knowledgeable they were and their compassionate interaction with families.

It’s hard to describe how devastating the COVID-19 pandemic has been for our patients and their families. The isolation is unspeakably sad. And now, nine months into the crisis, it’s emotionally hard, physically exhausting and very discouraging for those of us working the ICU floor. We lose a lot of our patients. We have higher acuity than we’ve ever had; typically we have maybe one patient per week who is so ill they require every machine we’ve got. Now it’s daily.

I won’t ever be able to forget the conversations I’ve had with my patients. They tell me how scared they are. In the absence of their family, I do my best to comfort them. They tell me where to find the money and what bills need to be paid so I can pass the info on to their family. Many of these conversations happen in the middle of applying urgent interventions. And many are the last conversations they have before they die.

One night, I helped with a patient I’d seen on the floor. On this shift, a newer Nurse had him. I noticed he starting to look worse, so I assisted her with some next steps, including calling the doctor to see if we could get him on 24-hour dialysis. My next shift, I had the patient. The minute I walked in I thought “he’s not going to make it through the night.” The day Nurse who handed him over to me said she didn’t think the family understood how sick he was. The physician hadn’t yet called the family, even though there had been a major change in the patient’s status. Sadly at St. Joe’s, we see this all the time right now. All of these duties are often falling on us instead of the physicians. The first thing I did was call the family. I asked, “How sick do you think your dad is? What do you understand about his illness?” They mentioned a minor condition and said they’d heard he was better. I had to explain the current situation. I said your dad is so sick he might die tonight. Then I had to deal with their shock. Luckily, we had a Nurse Practitioner on the floor who could further explain the patient’s status.

Thank god we talked to the family because an hour later the patient coded. We did CPR. I thought he would die, so I stayed there in the room and held his hand, trying to do what I knew his family would do if they could be there.

He made it through the night. I learned that he’d been a very active guy. Not sick before COVID. I had him again the next night and was hopeful for him. He was pulling through!

Two weeks later he was my patient again. He was ok, but there were some worrying signs. Then the next shift with him I again didn’t think he would make it through the night. I had to have that same horrible conversation with the family all over again.

I sat there in all my PPE and cried. I thought, “he’s not leaving the hospital. I’ll have to pump on his chest again and grieve with the family again.”

He died two days later.

COVID-19 is forcing countless families to make medical decisions they’re not prepared for. And we have to tell them these things over the phone…not together with them at their loved one’s bedside. One of the hardest things, of course, is when our patient is actively dying and we’re video calling with the patient. We hold the iPad feeling like intruders as they play wedding songs and grandkids say please come home.

Seeing death is part of the job. And it’s part of life. But we’re seeing traumatic death every shift. There are weeks where I’m doing after-death care on every patient on every shift.

It’s just hard.

We’re all burned out. We’re tired. It’s discouraging. We’re using all the medications we have. We prone them. We use blood thinners. Anything they say might help. Often nothing works. And now that we’re at capacity, we’re unable to give the same level of care.

I see people outside the hospital — even my family and friends — just going about their day, shopping, taking trips. It hits me hard that so many aren’t taking this seriously enough. I need them try harder to stay out of our ICU.

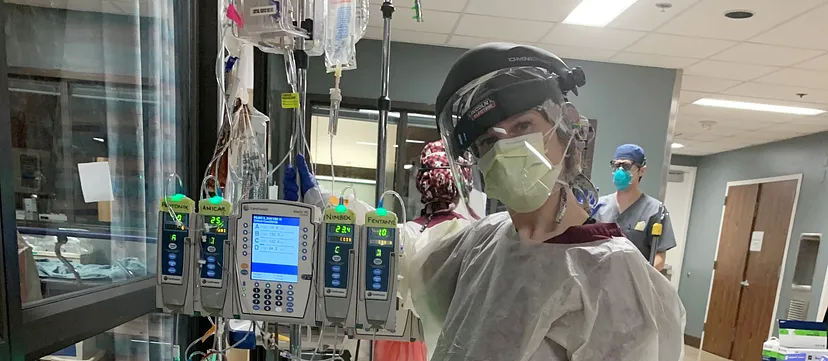

We’re doing more with less. I’ve had patients on monitors without working alarms — so there’s no alarm if oxygen saturation gets low or heart rhythms stop — just flashing light. But that doesn’t help if I’m with another patient and I can’t see the monitor. And we no longer have enough safety officers who are there to ensure that all intubations are safe, that donning/doffing is done correctly, that we’re not being careless, that we have all the supplies we need if we’re inside an isolation room. And doctors aren’t spending enough time with patients and families because the hospital saves PPE by having us do more of those functions. Our overflow ICU floors don’t have adequate lighting and lack IV pumps, monitors and other vital equipment. There are wires hanging out of the ceiling. We scrounge around for supplies every night.

And it’s only getting worse.